Home » How is Legionnaires’ Disease Transmitted? Who Is Affected?

Legionnaires’ disease is a severe pneumonia caused by the Legionella bacteria, which thrive in contaminated water systems. Since the first outbreak in Philadelphia in 1976, the illness has been recognized as a serious global health threat, particularly in hotels, hospitals, cruise ships, and public buildings where large water systems can harbor bacteria if not properly maintained.

Understanding Legionnaires’ disease transmission, who gets Legionnaires’ disease, and how to recognize symptoms is vital for prevention and treatment. With modern medicine and proper water system control, the risks can be minimized — but outbreaks still occur worldwide.

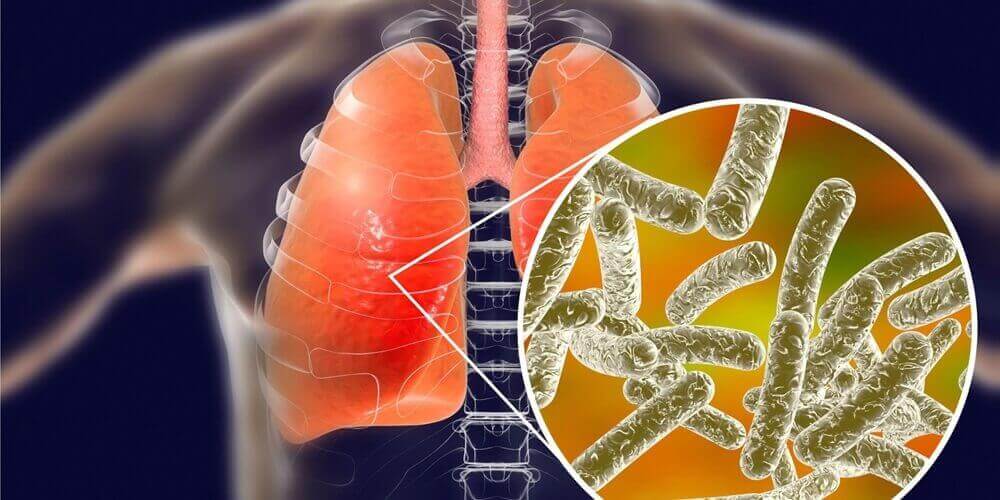

Legionnaires’ disease is a lung infection caused by inhaling microscopic droplets of water containing Legionella pneumophila. It is one of over 60 known species of Legionella, but L. pneumophila is responsible for the majority of human cases.

There are two main forms of illness caused by Legionella:

Both forms are part of legionellosis, but it is Legionnaires’ disease that poses the greatest danger to human health.

Unlike viruses such as the flu, Legionnaires’ disease is not spread from person to person. Transmission occurs through inhalation or aspiration of contaminated water droplets.

Common Sources of Infection

When these water systems are not cleaned and disinfected, Legionella can multiply rapidly, particularly in warm, stagnant water.

Anyone can develop Legionnaires’ disease, but certain groups are at higher risk:

For healthy individuals under 40, the risk is much lower. However, outbreaks in hospitals and nursing homes highlight the severe danger for immunocompromised patients.

Symptoms typically appear 2–10 days after exposure to contaminated water droplets. Early signs can resemble the flu or COVID-19, making laboratory testing essential.

Common Symptoms

If untreated, the infection can progress rapidly, leading to respiratory failure, sepsis, or even death.

Legionnaires’ disease is caused by Legionella bacteria, which thrive in warm water environments between 20°C and 50°C (68°F–122°F).

Legionella bacteria are naturally present in freshwater lakes and streams, but they become dangerous when allowed to multiply in artificial water systems.

Because symptoms resemble other types of pneumonia, diagnosis requires specific tests:

Fast and accurate diagnosis is critical, as early treatment significantly improves survival rates.

Unlike viral illnesses, Legionnaires’ disease requires antibiotics. Without treatment, the condition can be fatal, but with prompt therapy, most patients recover.

Commonly Used Antibiotics

Treatment typically lasts 10–21 days. In severe cases, hospitalization is required for:

The mortality rate ranges between 5% and 30%, depending on patient health and treatment speed.

Since there is no vaccine, prevention focuses on water system safety.

Key Prevention Measures

For individuals, avoiding poorly maintained hot tubs and public water features during outbreaks is recommended.

As climate change increases global temperatures, the spread of Legionella in water systems is expected to rise, making preventive measures even more urgent

Legionnaires’ disease remains a serious global health challenge, but with early diagnosis, effective antibiotic treatment, and strict water system management, the risks can be reduced.

By raising awareness of how Legionnaires’ disease spreads, who is affected, and the importance of prevention, both healthcare providers and the public can work together to minimize outbreaks and protect vulnerable populations.

Legionnaires’ disease is spread by inhaling tiny water droplets that contain Legionella bacteria. This usually happens in contaminated water systems such as cooling towers, showers, hot tubs, or large plumbing networks. The disease is not spread from person to person.

Early Legionnaires’ disease symptoms often resemble the flu. The first signs include high fever, chills, cough, muscle aches, and headaches. Some patients also develop gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea and nausea. Symptoms usually begin 2–10 days after exposure.

Anyone can get Legionnaires’ disease, but the highest risk groups are:

Legionnaires’ disease treatment requires antibiotics such as azithromycin, levofloxacin, or doxycycline. Severe cases may need hospitalization for oxygen therapy and IV antibiotics. With early treatment, most patients recover, but delayed care can increase the risk of complications.

Yes. Since there is no vaccine, prevention focuses on water safety and maintenance. Key steps include: